The Ringmaster

For over 50 years, Jearl Walker has stood center ring, guiding thousands through the amazing, spectacular, and awe-inspiring Flying Circus of Physics both in the classroom and beyond. And for scores of Vikings, he’s practically a household name.

You’d think that after everything Jearl Walker has accomplished throughout his career, after all of the accolades and the seemingly endless praise whenever he’s mentioned, you’d think that would be enough. Enough for him to sit back and acknowledge that he’s made it to rarefied air, hallowed even. That he’s among the best. That he has “it.”

But it’s not enough. And it likely won’t ever be enough.

He’s grateful, for sure. He just doesn’t think that way. Never one to rest on his laurels. For him, there’s always something else to learn, new challenges to overcome, more ways to improve.

Consider his experience as a college undergraduate.

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the early 1960s, Walker will admit that he felt — for lack of a better word — dumb. The prestigious university in Boston was an intimidating space. For one, to a Texas boy like him, New Englanders spoke another language altogether, he joked. But most importantly, the school was filled with some of the brightest, most promising minds in the country. Very smart students and extremely smart professors. Walker personally knows at least two people from MIT who went on to win the Nobel Prize in physics. In fact, he worked for one — Ray Weiss — as a senior. Weiss was responsible for discovering gravitational waves.

But Walker also personally knew students who crumbled under the weight of the institution’s prominence and sadly took their lives.

He distinctly remembers sitting in class like Charlie Brown, listening to his instructors drone on with indecipherable “wah wahs.” He was lost. So, he’d read his textbooks. Then read them again. And again. And again. Sometimes, at least ten times to fully grasp the concepts.

“I slept four and a half hours a day,” he said. “I studied all the time.”

He also remembers a kid named Ronnie. He hated Ronnie. “He wore a suit and tie to class every day,” Walker said.

He jokes that he’s suppressed much of his time during those formative years. Perhaps it’s a joke. Perhaps enough time has passed that the trauma doesn’t sting as much. We can’t tell. He jokes a lot. This one feels like truth, though, but Walker’s geniality and matter-of-factness belie any apparent PTSD.

But back to Ronnie.

“He wouldn’t take notes,” Walker said.

“He wouldn’t study for the exams. And he’d go in and make the highest grade.”

In comparison, Walker felt like he wasn’t up to snuff, like he was a big poser. It was imposter syndrome before it ever had a name. And for all that he says he’s forgotten about MIT, he’s never forgotten the 20-something Jearl Walker who felt like a dummy, who felt like he was completely out of his depth.

This might explain why the Jearl Walker we know today, Professor Jearl Walker, the inimitable Professor Jearl Walker, a man who, by all accounts, is a walking legend, is as humble as — they say — pie.

This also might explain why generations of students love him so dearly.

And to think: physics wasn’t initially the plan.

Walker has always been concerned with life’s big — often unanswerable — universal questions. Like how particles can go backward in time. Or the nature of time itself. In high school, in Fort Worth, Texas, he considered theology and philosophy.

“I think I would have starved to death if I went into those fields,” he laughed.

But he landed on chemistry. Went to MIT, supposing that would be his major. Earned one point above a failing grade on his first chemistry exam and promptly thought — perhaps

— life was guiding him elsewhere. Indeed, it was. So, he turned to physics, something that had also piqued his interest in high school.

“MIT almost beat it out of me,” he said.

But he soldiered through to earn his undergraduate degree and tried to bail on physics when he applied for graduate school at the University of Maryland.

“I applied to the astronomy program,” Walker said.

“But they mixed up my application, and I ended up in the physics department. And by that time, I just said, ‘Ok, I’ll stick it out.’”

If he hadn’t stuck it out, who knows who he might have become? He would have become something, for sure. Something great. But it’s likely we would have never known this Jearl Walker. The one who appeared on “The Tonight Show” with Johnny Carson. The one who wrote for Scientific American. The one who starred on the PBS show “The Kinetic Karnival of Jearl Walker.” And the one who created “The Flying Circus of Physics.”

It was the height of the Vietnam War, and hundreds of thousands of young men were drafted to combat, leaving colleges like the University of Maryland with a lack of instructors. So, the powers that be tapped Walker, a second-year graduate student to become a full-time instructor.

I loved it,” he said.

“I loved it.”

In one of his classes, he met a student named Sharon. One day, reeling after a recent quiz, she approached Walker with a gripe.

“She turned to me at the end of it and she said, ‘Jearl, how come none of this has anything to do with my life?” he recalled.

“I said, ‘Sharon, this is the fundamental clockwork in the universe. It has everything to do with your life.’”

She pressed him further. Give her examples. But he couldn’t think of any on the spot. That night he went home and created what would eventually become “The Flying Circus of Physics.” Even then, he knew he was on to something.

At the encouragement of a colleague, he sent what was then a technical report to Phil Morrison at MIT, who then encouraged him to pursue a book contract. In short order, he landed two offers. Morrison, by the way, is depicted in the film Oppenheimer. In one scene, he is holding plutonium in the backseat of a car en route to Los Alamos.

Nearly 400 miles away in Cleveland, a professor at CSU somehow got hold of the report and called the young instructor with an offer to teach at the young university.

At the time, Cleveland State was one of two schools offering tenure, so the choice was easy. They’d let him continue his work on his new book and give him the freedom to be the sort of professor he wanted to be.

“When I came here, I had no idea what a good teacher was because we didn’t have those at MIT. We didn’t have those in graduate school at Maryland,” he said.

“What I really learned at MIT and Maryland was how not to teach.”

But what he did know is that he loved to teach. And so, he worked to gain his students’ trust, remembering what it was like sitting in classes at MIT, feeling like a dope.

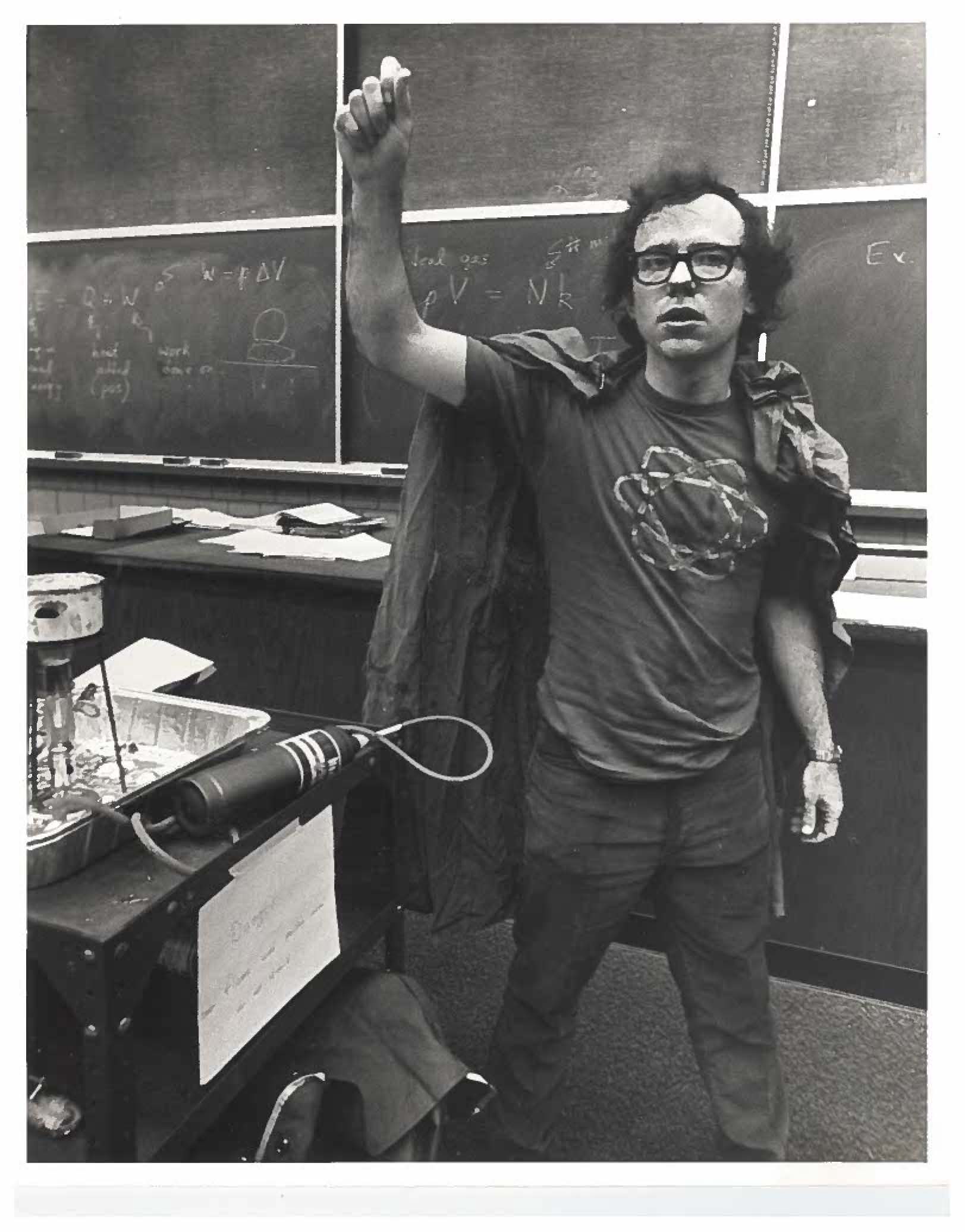

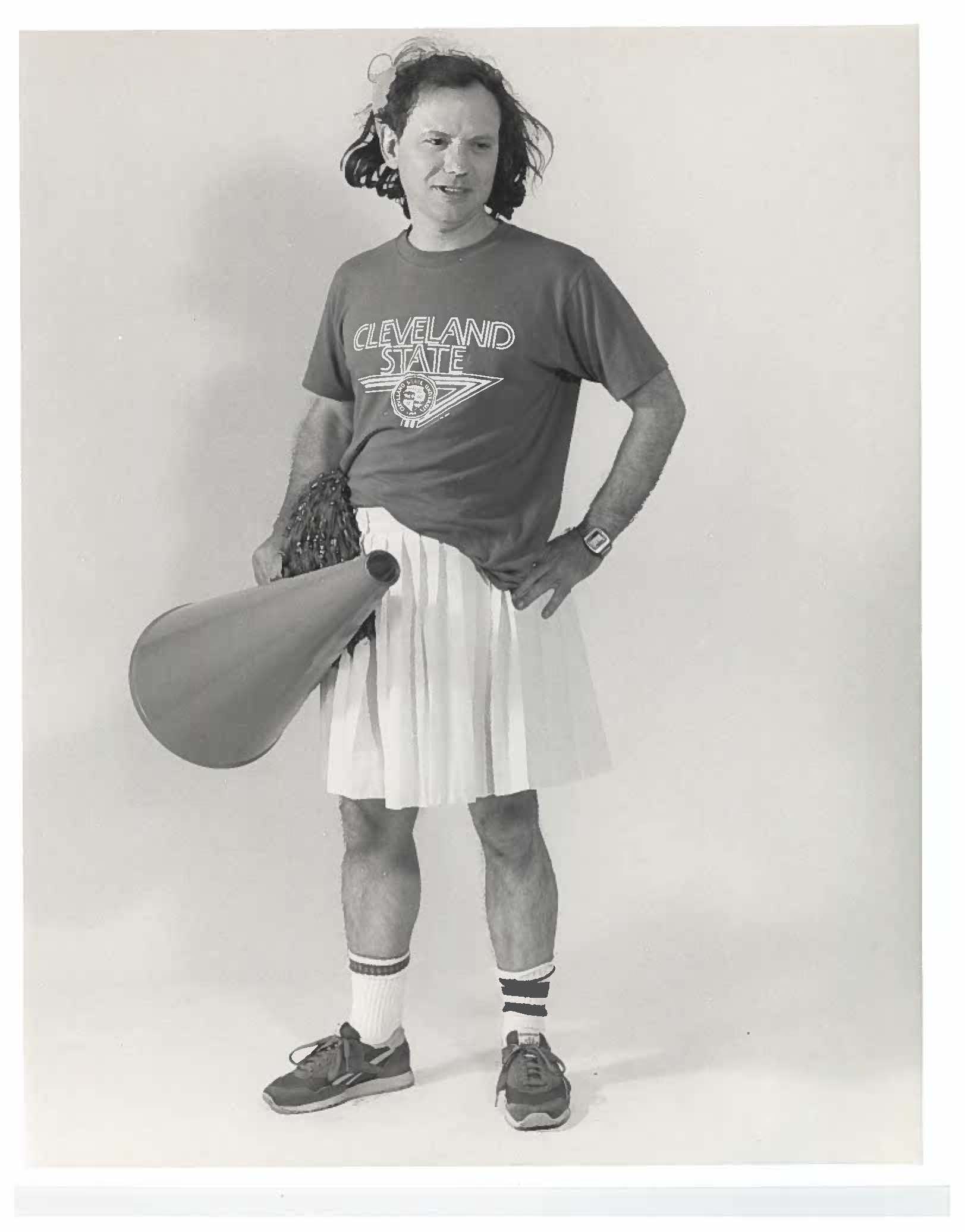

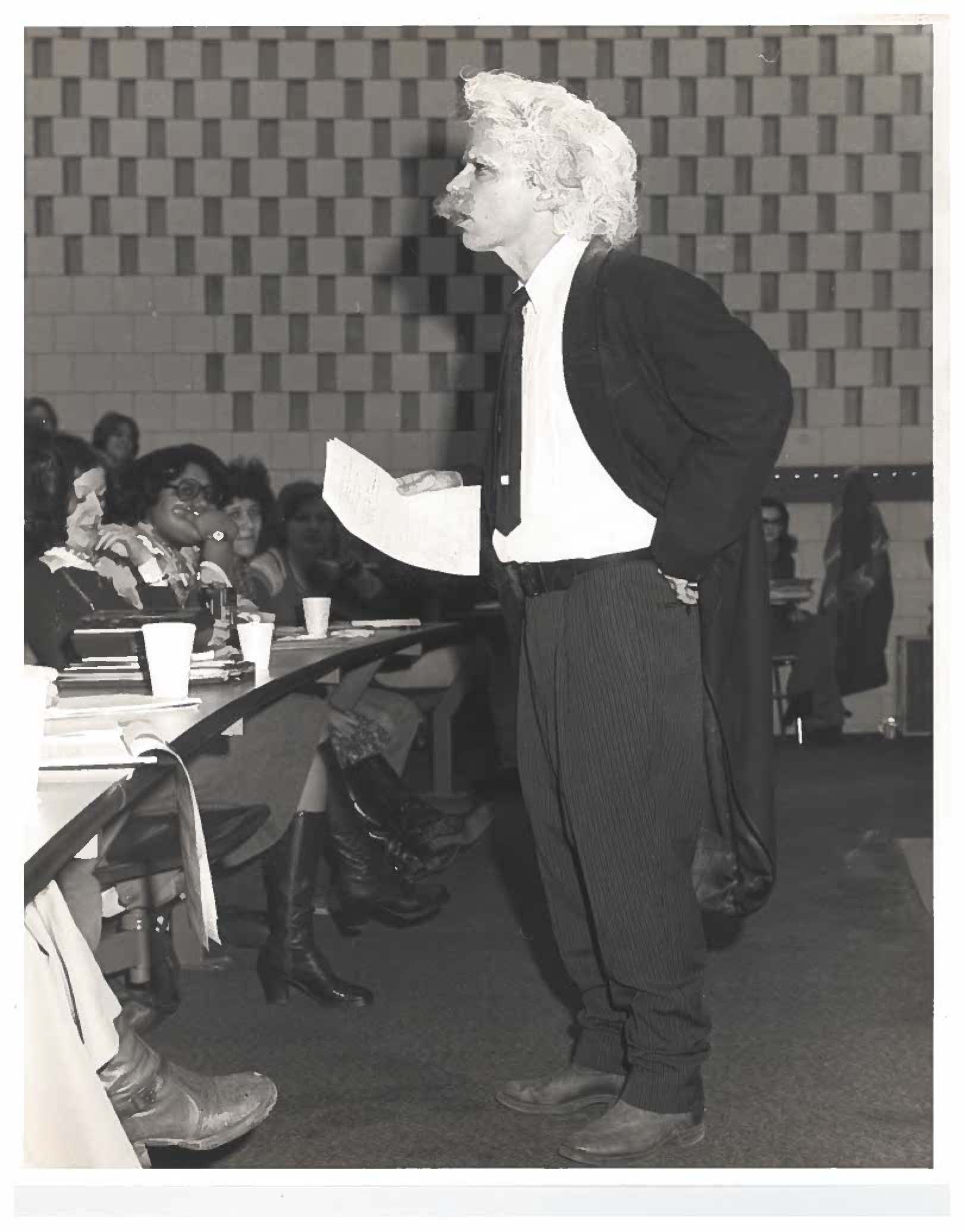

Although it took some time to win them over. He dressed as Albert Einstein. Became a cheerleader with a short, pleated skirt to teach the mechanics of a megaphone. (He still has the wig, by the way, and one of his students told him it was one of the grossest things she’d ever seen.) And who can forget sticking his hand in a vat of molten lead or the iconic bed of nails, which, to our surprise and a bit of horror, he still performs today as he approaches 80.

But they weren’t just stunts for attention; they were earnest attempts to make physics accessible.

That’s who he was then and who he is today, celebrating half a century at CSU.

“It went by in a flash,” he says.

“It seems like I was starting last year, but a lot of people have come and gone.”

He estimates that he’s taught roughly 25,000 students.

A few years ago, students started telling him that their parents were in his class. Then, a couple years ago, students started telling him that their grandparents were in his class.

“What I’m dreading, you can guess, [are having] great grandparents in my class,” he said.

“Maybe it’s time to bail out at that point.”

But that’s not happening anytime soon if he can help it.

He wants to face the blank stares in the classroom. He wants to take the students who feel like they’re ill-equipped by the shoulders and tell them they’re more than capable.

All these years later it’s still what drives him.

“I’m perfectly satisfied going in front of an audience of students and teaching them,” he said.

“I don’t need any great big thing to do otherwise. The students are the main thing.”